Dalton

He sort of detested everyone. Everyone, except me. He adored me, I never really knew why.

When I returned to Los Angeles after getting my undergrad degree at Berkeley, I got a job working for a wildly successful film producer and took a room for rent with my friend Dalton.

I lived with him all through my twenties: in that time, in addition to being my landlord, he became a dearest friend, a father figure, a mother figure, my mentor and ultimately my family. Dalton is the reason I did not become a mess.

Fifteen years my senior, Dalton was so full of life: I’m not actually a sharp enough writer to convey just how vibrant and electric his presence was. He was hysterically funny, brutally honest, beyond charming, and stylish (except the summer he got blond highlights, which even he admitted was deranged.)

He was caustic to the point of bitchy and absolutely unapologetic about it: to hear him talk shit about someone in his big Arkansas nelly twang was a masterclass, especially someone who deserved it.

The things he loved, he loved more than anyone reasonably should: if he found a shoe he liked, he bought 8 pairs, one in every color. He’d call in to vote on every reality show, the maximum number of times. He’d get a wild idea of making chili and serving it in mini bags of Frito chips and suddenly we were hosting a cookout for 50. Thanksgiving was art-directed to an inch of its life. Mashed potatoes in a martini glass! A shrimp boil served on newspaper in the backyard with no utensils.

He loved having lots of people around but he sort of detested everyone. Everyone, except me. He adored me, I never really knew why. I was young and annoying in all the ways Dalton traditionally loathed. But I was his: I was his young, annoying thing, so he had absorbed me into his mischievous and wild immune system and was protective of me.

Yet, he would temper his fondness for me in a surliness that I loved; he was always sort of performing “wicked step-mother” at me. I’d come home and he would hear me walking to my room and holler down the hall: “NOPE. Whatever you’re doing, its wrong! Better start over.” and then he’d giggle to himself.

I’d poke my head into his room and, without breaking his concentration on American Idol on the TV, he’d go “Noooooope.” I’d smile ear to ear.

One morning, he came downstairs where I was eating breakfast. He sized me up and down and declared, “Well, you’re never going to be better looking than you are today. Today is it. So you better use it. Whatever you can possibly squeeze out of this life with your looks, you better get it today.” He walked out the door, leaving me speechless with my Cheerios. “Today’s the day!”

When I decided on a whim one day to quit my lucrative Hollywood job and go to acupuncture school in 2002, Dalton never questioned it: parts of us die and are being reborn all the time. He supported my evolving–even if it meant evolving away from him–which only now do I recognize is the generosity of a true friend.

He essentially stopped charging me rent, silently adapted to my midterm and finals schedule by keeping the refrigerator more stocked than usual for certain weeks. During one particularly stressful semester, he decided we should go to Hawaii and arranged to use his miles to get us there, on a random Tuesday. I was miserable in Shang Han Lun class when i got a text on my pre-smartphone Nokia, “Go to LAX right now.”

He wanted more for me than he had for himself. He made me buy a suit and nice shoes (“You’ll need them.”) He thought I was too good for anyone I ever dated but still insisted he would walk me down the aisle someday; my moms would have to get over it. We sat on our back porch most summer nights; he chain-smoked (because of course he did) and we laughed and laughed. He radically expanded the scale of my life.

His spirit was wild; he was all Fire like I had never known. I didn’t know how much that fire cost him.

Twenty years ago this week, right as I was about to start treating patients, Dalton asked me to deliver some furniture out to Palm Springs. He said he’d meet me out there. But he didn’t make it. And when I came home, he wasn’t there either, but he left his cell phone on the counter, along with containers of his secret candy which he would never ordinarily let me eat and the refrigerator stocked full of home-cooked meals.

He wasn’t there because he had taken his life. He left a note, and in it said that I had kept him alive the last few years. It completely broke my heart.

People sent food but I couldn’t eat. A friend sent a Reiki practitioner to our house, which was such a lovely gesture, but I remember laying in my bed, screaming in my mind for her to leave.

I kept his cell phone with me at all times and people would call–well-meaning, loving friends, stricken with grief who just couldn’t believe it. They thought for sure there had been a misreporting, and he would answer once he saw their number. Instead they got me–furious and mournful–who would snap back, “No, he really IS dead actually.” Our friend Ruby eventually said “Russ, I think I’m gonna take that phone from you.”

I dropped out of school because the grief made it impossible. Grief dissolves qi, which is why the fatigue of mourning is distinctly and totally disabling. It drained my blood; my ruddy complexion turned to pallor (this is why the “color” we associate with the Metal element is white; translucent really, a perfect alabaster.) Dalton knew so many people that everywhere I went, I had grief projected onto me–“sad face” I would call it– because I was young and suicide’s blast radius does that.

I hid in the desert with Dalton’s best friend John and we shared grief. We would try to do just one thing a day but those first few weeks I couldn’t. We would go to Home Depot to buy a fan and I would be struck down in the aisle; I couldn’t remember why I was there.

All I could remember was: Dalton is dead. My feet would give out. I’d tell John, “I need to go home. I need to go home now.” And John would say nothing; he knew there was nothing to say. If it wasn’t me, it would be him. I’d go straight back to bed and so would he.

The grief had its way with me: I felt thrashed about by it, like wild ocean waves that would be occasionally calm enough that you’d feel it safe to swim and then knock you down when you didn’t see it coming. I resented it. You think you are done crying; surely there’s nothing left and then one song later, you are suddenly sobbing hysterically and endlessly as if it is the first tear you ever shed, as if you were brand new. Time doesn’t matter.

I ate a turkey sandwich, or just the bread. And then went back to sleep. It was 2 in the afternoon.

I came back to our home in LA. Everyday, another piece of furniture was removed; the art didn’t belong to Dalton, and nothing belonged to me. They repossessed his car. The plants died. The food in the cupboards rotted and I didn’t have the decency or the mercy to throw it away. The dishes piled up. I stopped using the heater–Dalton managed our temperature, and I didn’t feel entitled it to–so the house turned bone cold. The house froze in time, waiting for its real owner to come home.

I developed a night time anxiety about whether or not to sleep with my bedroom door closed. To leave it open meant I lived alone; I shared the house with no one. But to close it meant that I wouldn’t hear if he came home in the middle of the night, which some part of me assumed he would, the same small part of me that still does. I landed on sleeping with it cracked open just the slightest bit, so I could keep an ear open for his footsteps coming up the stairs, coming back to his room, coming home.

Eventually I started treating patients in the clinic but I was still in such pain, faking it. I worried that my sorrow would be felt in my treatments; that my grief would be in every needle. I asked my mentor, the great Dr. Yvonne Farrell, “Will I be able to help anyone if I am consumed by this much grief?”

She told me I should not worry about that, because she knew the truth I didn’t yet: grief is always a part of care. Care is love that is tending to its own fragility and transience. Care is connection, foretelling its dissolution. Care is the part of love that knows it will die.

The bond between care and grief is embodied in the acupuncture point Lung 9, Tai Yuan “Great Abyss.” As the Earth Point on the Metal channel, Lung 9 describes the inseparability between how we tend and nurture each other and how we let each other go.

LU-9 is the alloy between nourishment, mothering, and softness with the devastation of grief, the coldness of loss. The taste of Earth is sweet: the sweetness of saying goodbye. The deep, joyful tenderness and mercy that emerges from the fact and inevitability of seeing something you love die.

As the years passed, the sweetness surpassed the grief and I worked to make sense of his death. Things became clearer in hindsight and from the detective work we all do after someone dies by suicide. I posthumously diagnosed him. I rationalized his choice and justified it to people who were still angry or devastated.

I thought if I could reason with it or understand it intellectually, then I could forgive him, and that might ease the pain of it for me. It felt generous and adult to endow his death with meaning and sanity and goodness.

But as I’ve gotten older, I feel less compelled to mine reason or meaning out of death, because trying to do so is often just a way to feel less; to convince myself I am not entitled to be hurt. I wanted to rationalize his pain so as to negate mine. Now I think both pains have dignity and deserve grace; I like them living together.

My heart broke when he died. It’s still broken. It feels important that I not lose that, that I not brush it aside, or intellectualize myself out of it. Twenty years later, I can just be within the loss, like an early morning swim in a smooth, still lake.

Loss asks us to release human ethics or reason: the cosmos gives and takes according to its own grace and intelligence that is ultimately unknown to us, and unknowable. We must learn to face the darkness without demanding we find light there.

This is Autumn. The waning light is the reminder that everything is impermanent, fading and delicate; no part of life is yours to keep. We must allow the things we love to die, and slip away with ease, like the fragrant warmth of blankets pulled fresh from the dryer. Of course you’d keep them if you could. But you can’t. They were never yours.

And in letting go, you feel the clarity and poignancy which is the point of grief: loss gifts you the radiant beauty of living as only seen from the edge of its own vanishing.

The Sun sets early and you say, “It was beautiful. It wasn’t mine, but wow it was beautiful.”

I went to go visit John a few weeks ago. He had digitized some old photos and we blasted through them. We laughed about Dalton–his style, his frosted tips, that summer he was an ill-advised blond. The year he broke his foot, we’re still not totally sure how; his story never really added up. Pictures from Hawaii. From Cape Cod. The zoo. It wasn’t so sad anymore. It was all love.

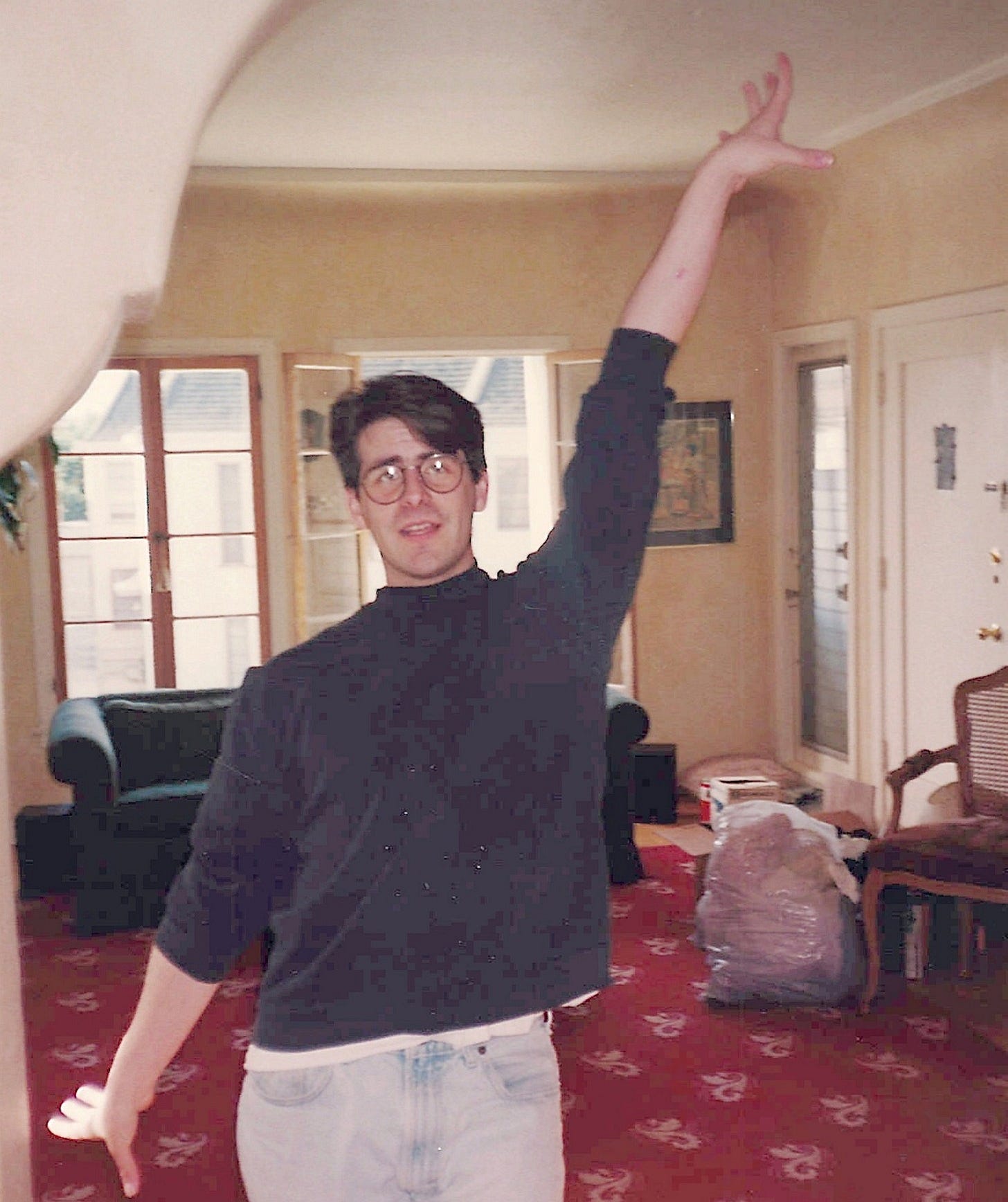

We landed on one particular photo and there was something about Dalton in it. He was posed just so, something about the arch of his hand, almost impossibly bent, a little gay flourish. He was so fully himself in this photo, from his turned out feet to the effete tip of his pinky finger; whatever spirit he was in this lifetime–whatever tortured but beautiful magic that innervated his body and brought him to life¬had been entirely captured by this cheap 1998 disposable camera, and printed at some CVS photo department on Santa Monica Blvd.

I couldn’t help but cry. John said, “I know, right?” I had forgotten it. That spirit didn’t go anywhere. I didn’t lose it. I had just forgotten. And now here it was, alive and in full fluorescent display, right here, just for me. I didn’t lose a thing. What I loved is still here.

It’s in the places I’ve lived that he would have hated. It’s in my relationship with my idiot boyfriend whom he never met. It’s in John and our friends who loved him. It’s in my work with my patients; it’s in my care.

Dalton is in my acupuncture studio, in the wood, in the plaster, in the stars. He’s in the clouds that I see in the morning when I take my dog Backpack for a walk. He’s in the wind. He is everywhere; just not in his body, just not chain-smoking on our porch, the one place my ego had really, really wanted him. But he is everywhere else.

The 20th anniversary of someone’s death is a totally arbitrary and meaningless milestone.

But I’m thinking about him today, and I wanted to write about him. Words give form. He’s a significant part of Poke Acupuncture. It matters to me that he is written about and documented into the fiber of this project. (He died before social media; he would have developed such an unhealthy relationship to it.)

Every treatment I have ever given, and every word I have ever written, is soaked in both my grief for him, and my love. His sadness, his laughter and his hope is braided into the DNA of my work. Every acupuncture point I have ever needled is in celebration and gratitude to him. Dalton is in everything I do.

I placed a needle on a patient’s wrist this morning. LU-9, “Great Abyss.” I could feel Dalton watching. He was smiling, and whispered into my ear, “NOPE. You’re doing it wrong. No, no, no. Nooooooope.

Better start over.”

Dalton Robertson 5/14/63 - 9/23/05

thank you for this, really beautiful. my best friend committed suicide in our twenties, its a certain texture of grief that lives on in so many unanswered ways. i just want to say and im sure you know this - just as Dalton gave you space to be who you are, you do that everyday with your care. when you take a seat to explain the poetry of the points after inserting them, it’s the same deep care of the person who would buy you a ticket to hawaii. 🖤

Really beautiful, my best friend suicided when I was in my early 20’s. It was shattering. You really capture that near limitless grief and how it carries on in us. As if we are no longer living our lives just for ourselves any longer.